Should Schools Separate Sex Ed Classes by Gender?

From the Future of Masculinity weekly newsletter, where our community’s hearts and minds come together each week to do the work, tell the stories, and build the blueprint for a future where men and boys experience less pain and cause less harm.

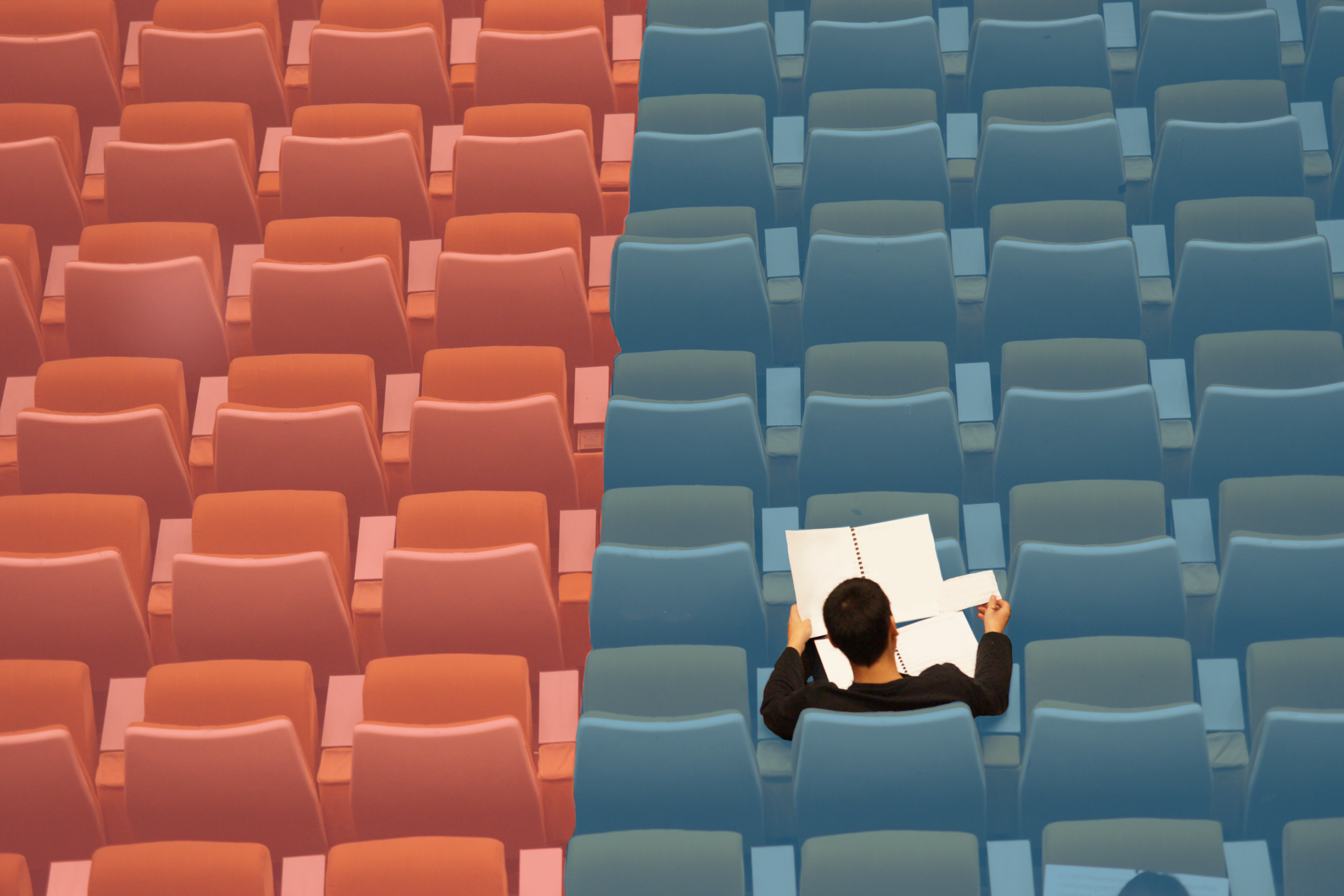

Sex ed—it’s a class that divides people.

If you talk to adults about their experience with sex education at school there seem to be three camps: some will tell you that they were only taught easily forgettable talking points, others actively try to forget the more damaging messages they learned, and the remaining few would give their education a positive review.

Sex education has changed over the years, but one thing has remained constant: the separation of boys and girls during sex ed class.

But the rise in popularity of the sex-positive movement has made a lot of people take a closer look at the structure and content of sex education in schools.

Sex positivity, something we unpacked with our friends at Marlow, promotes the idea that everyone should be able to engage with topics of sexuality, health, and pleasure with respect and without shame or stigma. This movement encapsulates gender identity, sexual orientation, nudity, relationship styles, body positivity, safer sex, reproductive equity, and importantly sex education.

So if schools use a sex-positive approach that is both inclusive and comprehensive—does that mean sex ed classes should be together or separate?

We need to examine some of the underlying assumptions and intentions and weigh the pros and cons of single and mixed-sex education.

Pro: Separating boys and girls may create a more comfortable space.

While all youth should receive consistent and comprehensive sex education, does that mean all youth experience sexual health the same?

A gender-neutral approach doesn’t acknowledge the unique ways different people experience sex, sexuality, and relationships. By separating by gender educators may be able to focus on specific topics that are of particular interest to boys and girls and allow for peer discussions that come from shared experiences.

Those conversations are made easier when the students feel comfortable knowing that their peers are going through similar experiences. The ability to openly divulge shared worries, fears and experiences give opportunities for in-depth conversations on sensitive topics and relational learning that otherwise might not have happened.

Con: Having two binary options can alienate 2SLGBTQ+ students.

Let’s be honest—we’ve let down 2SLGBTQ+ youth.

Schools have had a long track record of excluding 2SLGBTQ+ serving information or in worse cases demonizing it.

Less than 7% of 2SLGBTQ+ youth in the United States report receiving sex ed that included information on gender identities and sexual orientation. This isn’t surprising considering governments only mandating the bare minimum (Florida goes so far as to ban discussion of sexual orientation and gender identity in elementary schools) with Canadian provinces not much further ahead in only going as far as teaching ‘tolerance’ instead of promoting acceptance and providing in-depth information.

When we ask youth what kind of sexual education they need, they answer.

“My teachers excluded mandatory information about my sexual health. There was a lot of information missing. On top of that, they used outdated and incorrect information. The lessons excluded LGBTQ+ students and are not clear enough on what little information they have about sexuality. Teachers are not clear enough on certain things and can make it seem scary or unbearable”

This is especially important right now, as there has been a wave of anti-trans legislation in the United States, which overwhelmingly targets 2SLGBTQ+ youth. This exacerbates the fact that trans youth are struggling already with 90% of trans youth hearing transphobic comments on a daily basis and more than half of them have considered suicide.

2SLGBTQ+ youth already experiencing stigma, dismissal, and lack of sexual health education being separated by gender in sex ed completely ignores the existence of students who identify outside of the gender binary and further perpetuates heteronormativity (the assumption that everyone is heterosexual).

Are youth going to receive appropriate sexual education if they are forced to side with either ‘boys’ or ‘girls’ class? Doubtful.

Are they going to feel dismissed, shamed, and unheard by forcing them to pick a class? Undoubtedly.

“In sex ed, boys and girl were separated…that’s not good for trans folks in the classrooms!”

Con: They’re probably not very focused on sex positivity or gender equity.

When educators separate classes by gender to teach specific topics, an unintended consequence reinforces the idea that there are ‘women’s issues’ or ‘men’s issues.’

Students benefit from learning about the experiences of all genders because it equips them with an understanding of other people’s bodies, which reduces stigma and builds empathy.

When youth were asked to describe what kind of space sex ed class should be like, a common thread was an environment where everyone is encouraged to learn beyond their own experiences.

“It would look more like people sitting in a circle, people of all orientations and genders, rather than in rows/desks. I think we would learn how everything someone feels is normal and that no one is alone. It would teach everyone the importance of being safe. It would make everyone more aware of things about people of other genders and orientations.”

Separating classes by gender opens the opportunity for misinformation and can unnecessarily alienate students from their peers of other genders.

After all, a lot of misunderstandings around common sex ed topics like the gender spectrum, menstruation, and sex are the root of gender inequalities and discrimination.

And make no mistake—gender equality needs to be part of sex ed. Not only does sex get safer when sex ed covers inequalities, but these lessons also have a positive impact on larger social issues.

As Action Canada for Sexual Health Rights explains, gender empowerment-focused sex ed is an effective intervention for a wide range of positive outcomes, such as early marriage, sexual coercion, intimate partner violence, homophobic bullying, girls’ agency, school safety, sex trafficking, and gender norms.

Kinda-sorta-not-really pro: Teachers can add more value when teaching classes of the same gender.

Students who are taught by educators of the same gender might feel more comfortable and may receive a more nuanced or accurate education when the teacher can speak from experience.

In theory, this makes sense. After all, people with real-life experience have a better understanding of topics and provide personal insight.

…But are teachers really comfortable?

With only 16% of Bachelor of Education programs in Canadian universities requiring students to cover sex ed training, educators can feel ill-prepared and under-supported when teaching sex ed.

And students can sense their teacher’s levels of comfort or negative attitudes.

“If your teacher, who’s a grown-up can’t talk about it, how are you? That gives you the impression that, oh I’m not really supposed to talk about it”

These attitudes impact youth greatly. Especially considering youth expressed that feelings of shyness, embarrassment, or awkwardness as factors that prevent them from accessing information or developing skills.

It’s a known fact that teachers often focus on what they feel comfortable with which is: body image, reproduction and birth, abstinence, genital names, puberty and menstruation, and personal safety.

The common denominator for all of these topics? They are all very objective, staying in the realm of science, definitions, and anatomy. The subject matter allows a certain amount of distance between the educator and the information because you are sticking to the concrete facts of life.

Meanwhile, the topics teachers were least comfortable teaching all cover the very human (subjective) experiences of sexual health like sexual pleasure and orgasms, masturbation, sexual behaviour, porn, attraction, love and intimacy. Those concepts are a lot more nebulous and are difficult to be objective about because we each experience sexuality differently.

Interestingly, these least covered topics also happen to be what students express the most interest in learning. Coincidence? We think not.

Only 28% of high school students and 44% of junior high students felt that most of the sexual health topics covered in school were of interest to them.

So if educators’ comfort levels depend on the topic they’re teaching, do students—or teachers—actually benefit from separating the class by gender?

Where does this leave us?

You’ve probably picked up on a common thread across all of the pros and cons: comfort.

The debate for separating sex ed classes can really be boiled down to the question—who will be comfortable and who will be uncomfortable?

While it’s true that learning requires us to step outside our comfort zone, not all discomfort is the same. Some students might be uncomfortable from the get-go because sex is a touchy subject (remember that stigma we mentioned earlier?), but some students might be uncomfortable because they feel their school or educators are disregarding or even shaming them because of their behaviours or identity.

And those types of discomfort result in very different outcomes.

The way we structure sex ed classes and content can either push students (and teachers) to the stretch zone, where they feel curious, nervous and willing to learn, or it can push some students to the panic zone where they feel anxious, stressed or overwhelmed.

To conclude this post with a nod to gender-specific or mixed-gender spaces would also perpetuate a binary. One takeaway is that contemporary sex ed may be improving, but it is still lacking.

Going through the pros and cons of separating classes makes it clear that if sex education is ever going to get to being sex-positive, we must ensure that we are stretching and creating environments free from panic.

Written by Sarah Andrews, Next Gen Men’s Marketing Manager