How Men Fit Into Feminism Across History

This article that was originally featured in the Future of Masculinity Zine. Grab your very own print or digital copy.

BY VERONIKA ILICH

Men’s involvement in feminism pre-dates our Next Gen Men community by more than a hundred years. From the UK to the US, as early as the mid-1800s, there were men who supported women’s right to vote.

The First Wave of Feminism

Men’s support for women’s suffrage was certainly slow and sparse to start — and indeed many men found the idea laughable — but it grew steadily toward the turn of the century.

W.E.B. DuBois: American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist. (Image: Hutchins Center)

Change came thanks to the activism of the suffragettes. Women won the right to vote, to run in elections, and to sit on juries, and support for these changes among men did exist. Kimmel and Mosmiller, in their seminal 1992 book, compiled over 1,000 letters, journal entries, newspaper articles, and other writings of men in support of the movement — from notable names like W.E.B. DuBois and Walt Whitman to less well-known religious leaders, judges, journalists, and everyday men who affirmed their support for women’s suffrage, in public and in private.

Yet men’s support, even where it existed, was uneven.

Some were true champions of the cause, yet others, despite their public proclamations, in private were hardly models of ethical behaviour. Nor did all male supporters advocate for women’s suffrage out of a true desire for women’s equality. For instance, some men only supported white women’s right to vote as a potential counter-balance to the growing rights of African-American men and incoming European immigrants. Male allies were not alone in these attitudes — many wealthier white women likely also saw their right to vote as a means to protect the interests of their racial and class groups, rather than as solidarity with their sisters.

Did these men call themselves feminists? Actually, no, and neither did most suffragettes. Feminism as a term wasn’t popularized until much later, when the movement started to connect more women’s issues together.

In fact, first wave feminism was quite fragmented. Suffragettes did not agree on many other women’s issues, from rights within marriage to reproductive health. They did not always see these issues as equally important, or even as issues that women should care about. Nor were they necessarily supportive of working class, Black, or Indigenous women’s rights.

In short, first wave feminism was both divided and silent on many issues, and men’s involvement reflected this fragmentation.

The Second-Wave Feminism

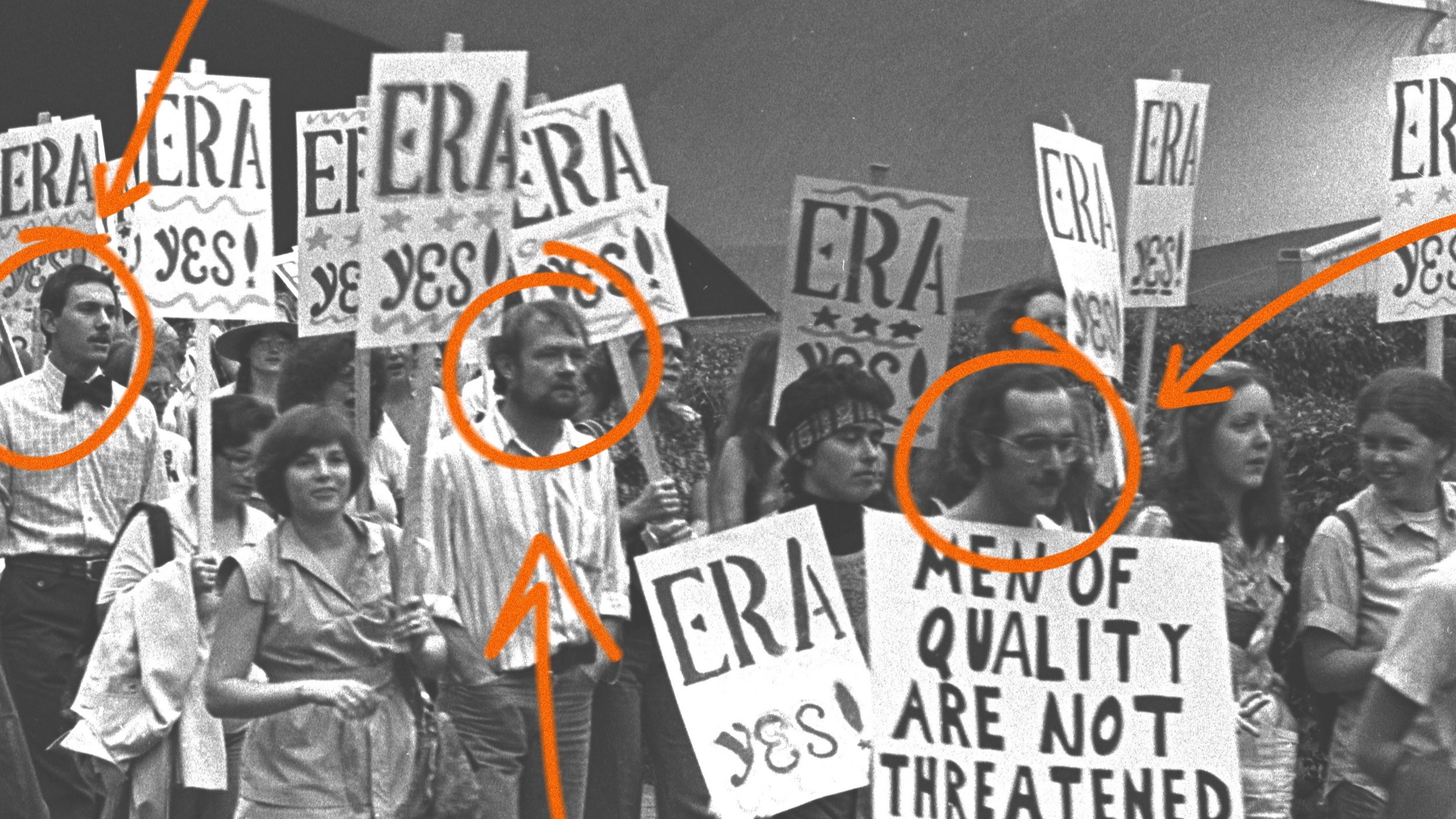

The second-wave feminism of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s also had vocal male allies, but this time both women and their allies created firmer connections between varying facets of women’s oppression. In this phase of the movement, they worked to make clear that access to reproductive health care, the prevalence of sexual violence and harassment, and the importance of maternal health, pay equity, and achievement gaps were all clearly and strongly connected.

With this focus, it was necessary to shift the collective paradigm away from thinking that violence against women was a ‘woman’s issue’, something that good men can help with here and there. Instead, they set out to show that it is fundamentally just as much a men’s issue, which men have a responsibility to solve.

Now, while many men have yet to take up the cause, international organizations of men working to end men’s violence against women, like White Ribbon and Men Engage, do exist. In many ways, the world today is a far cry from the world of our suffragette sisters.

Yet still, I wonder why there aren’t more men who call themselves feminists today.

Where are Today’s Male Feminists?

Perhaps it is because the feminist asks of men — to divest from male domination, take accountability for male violence, and be allies in the struggle — were not clear enough as to what men stood to gain. I understand that this is a potentially inflammatory statement, as it’s true that we should not have to pander to men to receive recognition of our humanity. Still, it is also a fundamental truth that people care more about issues when they understand how they are directly affected.

“Boys need healthy self- esteem. They need love. And a wise and loving feminist politics can provide the only foundation to save the lives of male children. Patriarchy will not heal them. If that were so they would all be well.””

I would argue that it’s time for another shift: for men to understand the ways in which patriarchy harms them too, to see themselves as stakeholders, instead of allies, in gender equality.

With that shift, I believe far more men would join the movement. Like women in the second wave did, men today need what bell hooks calls consciousness-raising. They need more discovery, more exploration, more awareness. Subjugating women isn’t baked into them, it’s not a given in any person’s worldview. When asked the right questions, men will start to see how the threads of patriarchy have been woven into the fabric of their lives and finally begin to unravel them.