“Inside, I Really Feel Hurt”

By Jonathon Reed

On January 29, 2017, six Muslim worshippers were killed at the Islamic Cultural Centre of Québec City during a peak of anti-Muslim hate crimes in Canada. The attack in Christchurch last year—the deadliest mass shooting in modern New Zealand—was inspired by the Québec shooting, and in turn led to copycat massacres at a synagogue in California and a mosque in Texas, and a failed attack on a mosque in Norway in the months following.

On January 29, 2017, Rehan was ten years old.

“I remember when it happened,” he said on the podcast. “That night, I actually started crying because I was like, ‘What if that ever happened to me?’”

Rehan is thirteen now. As an Ahmadi Muslim, he participates in prayers, holidays and ijtima gatherings at his local mosque. He plays on more sports teams than I can keep track of. He loves his mom’s roti.

He told me he first remembers experiencing Islamophobia and anti-Muslim stereotypes alongside the rise of ISIS in the media, and described old jokes about the Takbīr and terrorism blending into current youth culture narratives about gun violence in schools.

“That really hurts my feelings emotionally. Even if they say it as a joke, it still hurts me, like some people in my class will be like, oh no, school shooter, terrorist, Muslims. I laugh along with them but inside, I really feel hurt. At first I was okay with it. If I’m being honest, at first I was saying it too. Because I thought it was a joke and everything. That was when I was young, but now that I’ve matured, I’ve realized that you shouldn’t say it because you’re really talking about yourself in a way. You shouldn’t really use it against yourself…You should be proud of yourself, you know?” — Rehan on the podcast

I also spoke with Fatmeh, a youth worker at the Edmonton Mennonite Centre for Newcomers. “I’ve had girls come into my program after school and say, someone just tried to rip off my hijab on the bus, you know, or someone physically attacked me or verbally assaulted me,” she said. She pointed out that Muslim girls and women visually represent Islam when they wear a hijab, and are therefore often on the frontlines of anti-Muslim sentiment.

“Because of that,” she added, “we see a lot of that feeling of the need to hide your identity among the boys. Feeling scared of people finding out who you are.”

At this point of his life, you can actually hear a lot of pride in Rehan’s voice. But you can still feel his sense of injustice in the face of joking stereotypes and rising violence. It’s not hypothetical. It’s a current that runs from his family and his mosque through his class at school directly to his heart.

I was on my way home from a festival when I read the news about the shooting at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando in 2016. My knees buckled to the ground and tears started running down my face. I still remember sitting with my forehead against the glass window of the bus, watching Toronto fade into the distance and feeling like nothing would ever be the same.

In some ways, that’s how I imagine Rehan on January 29, 2017. So when I think about his experiences with Islamophobia, I remember how pride in my identity hasn’t always outweighed the threat of violence. It’s a similar feeling to the way Rehan identified with the victims of the Christchurch shooting. “Imagine if you were praying and a guy was shooting,” he said. “I don’t know what I would do, if I would just leave the prayer, which is like, really bad. Or if I would keep on praying and pray to God, please don’t make me die.”

“It’s just very scary.”

Anti-Muslim jokes and stereotypes carry the weight of tangible violence because they’re part of the same pattern. A poll in 2015 found that 44% of Canadians felt negatively towards Muslims. According to data collected by Statistics Canada, hate crimes against Muslims grew by 775% between 2012 and 2017. That means that Québec City wasn’t an anomaly, nor was Christchurch. These acts of violence that loom so large in Rehan’s cultural memory are part of a system that normalizes white supremacy and racism, a system that Rehan navigates every day.

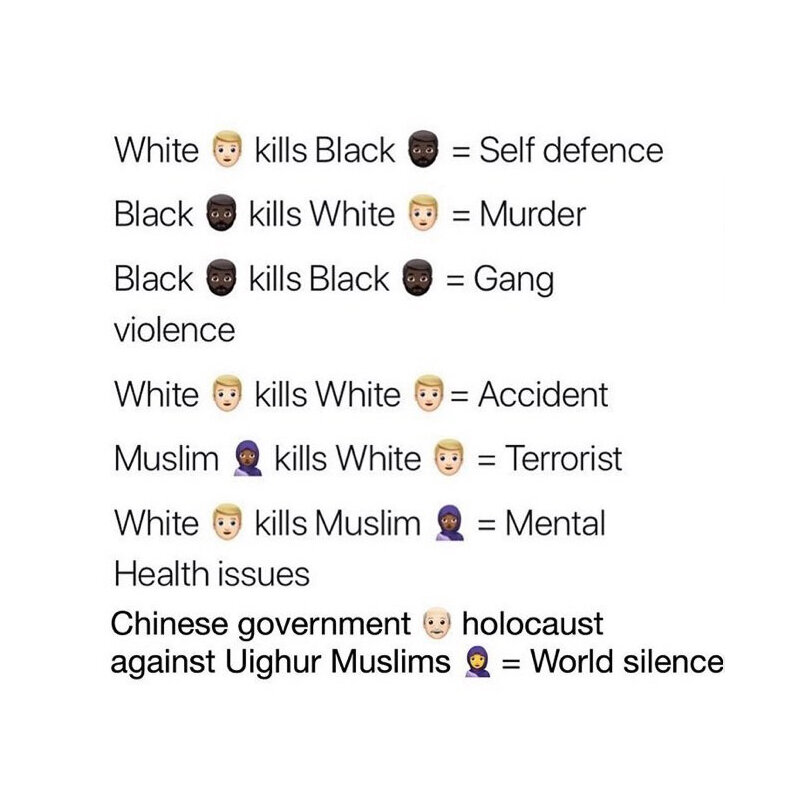

“Can I add something? I just want add on an important thing that you need to listen very closely to. So, when a white person kills a Black person, it’s called self defence. When a Black person kills a white person, it’s called murder. […] When Muslim people kill white people, it’s terrorists. That’s what I was mentioning before. And when white people kill Muslims, it’s mental health issues. Most of the time they just want to do it because they hate Muslims. And that’s not fair.” — Rehan on the podcast

Meme about media racism adapted to include Uighur Muslims and shared on Rehan’s Instagram story

In our conversation, Rehan connected this analysis of mainstream racism to the ongoing oppression of Uighur Muslims in China, but it’s also relevant to Fatmeh’s work with refugee families in Edmonton over the last few years and white supremacist groups’ involvement in the pro-gun rally in Virginia this past week.

The point is that violence doesn’t end just because you cross a border, and just because we can point to a historical event and say that it was an example of Islamophobia doesn’t mean that it’s not still happening now. It is still happening.

We need to talk about it.

“The biggest thing that teachers can do,” said Fatmeh, “is create safe space for dialogue. You know, encouraging opinions but making sure that those opinions are not hurtful or offensive.” She recommended that educators look into the Centre for Race and Culture, an Edmonton-based organization that seeks to create an inclusive society free of racism through intercultural understanding and education.

Rehan talked about leveraging social media to increase awareness about social issues like the Uighurs, and turning that knowledge into action by getting a permit to protest at governmental institutions. “It’s about taking a bigger responsibility,” he said, “a bigger act upon yourself.” If nothing else, he encouraged others to research or ask friends about Islam and what has been going on in their cultural history.

“I think it will help a lot. If my friends weren’t my friends right now, they probably wouldn’t know about the Chinese Holocaust. Some of them started posting on their social media too, and I was very happy. I even told them, like, thank you, because they actually took the initiative to talk about it and they weren’t embarrassed, and they did it all for me.” — Rehan on the podcast

“I think it’s very beneficial in terms of building a harmonious society,” added Fatmeh. Having friends with different backgrounds from your own develops your understanding of other cultures and religions, but it also means that you have relationships based on interests rather than shared experiences of trauma. “It’s important for youth to have their identities be more than just their challenges,” she explained. “If your friendships are all based on your challenges, then that becomes your identity and that becomes your life.”

Perhaps we know what it looks like when people’s challenges become their identity, because we have seen incel Alek Minassian commit Canada’s deadliest vehicle-ramming attack, misogynist Alexandre Bissonnette commit Canada’s worst mass murder in a house of worship and anti-feminist Marc Lépine commit Canada’s deadliest mass shooting. These men connect white supremacy to misogyny in a narrative that I would get into if I wasn’t exhausted of writing about radicalization and violence.

In October, feminist writer Joanna Schroeder published an article in The New York Times about fortifying boys to resist the allure of being part of a brotherhood in online forums based on racism and sexism. She spoke with Jackson Katz, an educator long involved in ending male violence.

“To counteract the seductiveness of that appeal from the right, we need to offer boys a better definition of strength: that true strength resides in respecting and lifting up others, not seeking to dominate them.” — Jackson Katz

Islamophobia is on the rise in Canada. It’s perhaps most visible in the forms of explicit violence such as the massacre in Québec City, but it also manifests in schoolyard jokes and well-meaning teachers and whitewashed media. Girls having their hjiabs torn off. Refugees being told to leave. Kids who can describe racism as easily as their evening prayers.

When you hear these kinds of things, it can be hard to know where to start. But while this has been a story laden with violence, it’s also a story led by the clear voice of an idealistic thirteen-year-old who is aware of social issues around him, brave enough to stand up for others, and early on his journey into making the world a better place. Start by listening to him on Simplecast or wherever you get your podcasts. Then take action in your own community.

Also, follow him on Instagram.

Written by Next Gen Men Program Manager Jonathon Reed as part of Breaking the Boy Code. Also published on Medium.

Breaking the Boy Code is a feminism-aligned publication on masculinity on Medium, and a podcast on the inner lives of boys on Apple Podcasts, Google Play and Spotify. Follow @boypodcast on Twitter and Facebook for podcast-related updates and masculinity-related news.