The Influence of Influencers: How to Tackle Andrew Tate in Schools

“It feels like our male students are drifting further and further from where we want them to be,” a school counsellor wrote to us in the middle of the school year, “and it always comes back to Andrew Tate.”

You’ve heard his name before.

Depending on who you talk to, he’s either a successful entrepreneur and unapologetic role model who’s been unfairly cancelled for speaking the truth—or a toxic megalomaniac and convicted sex trafficker who made his fortune grifting his followers and exploiting young women.

Last year, Andrew Tate had more searches on Google than Donald Trump, Kim Kardashian and Queen Elizabeth II put together. His dominance in the lives of boys and the impact of his rhetoric on masculinity culture can’t be understated.

The issue, however, is less Andrew Tate as an individual and more Andrew Tate as the latest example of an ongoing cultural shift towards re-entrenching the status quo of gender hierarchy and masculinity ideology.

Schools are seeing this firsthand. Whether it’s in their disengagement in the classroom, a resurgence of sexist jokes towards female classmates, or a slide toward extremist views, it’s clear that boys and young men are looking for guidance.

They will find it at the hands of exploitative hustlers—or in conversation with sensitive and committed educators.

Let’s make it the latter.

Teachers should be authentically curious about boys’ perspectives on Andrew Tate.

“The masculine perspective you have to understand is that life is war,” Andrew Tate declared in an interview with Chian Reynolds. “And if you’re a man who doesn’t view life as war, you’re going to lose.”

This rhetoric catches boys’ attention because they’re quite familiar with the sensation of unexpectedly finding themselves on a battleground. Whether those battlegrounds are defined by healthy competition or unwelcome violence, they usually share one thing in common: there are winners and losers.

Nobody wants to lose—least of all teenage boys.

Curiosity is the first of Next Gen Men’s core values for a reason. Positive change is only possible when we position ourselves alongside boys rather than against them. We need to see what they see. We need to help them feel heard.

We can’t head into conversations with boys about Andrew Tate with our minds already made up. We need to operate from a place of steady openness and empathy, because once boys know we respect where they’re coming from, they’ll feel more ready to be challenged.

Andrew Tate says his messages are positive for boys and young men. Here’s why that’s impossible.

What we see most often among teenage boys who support Andrew Tate is the belief that you can separate the good from the bad. For example, one of the youth in The Man Cave’s research on boys’ perspectives on Andrew Tate wrote: “I relate to the fact that he is able to inspire young individuals around the world to stand up for themselves and improve themselves, but I don’t resonate with his toxic, sexist, and misogynistic side of conversation.”

Boys aren’t entirely wrong about making this distinction. Some of Andrew Tate’s more contentious claims are indeed part of an intentional rage bait strategy that spurs social media algorithms into promoting his content, and a fair amount of his content does revolve around less immediately harmful tenets of traditional masculinity like discipline, grit and self-improvement.

The problem is that regardless of their intention, the messages of influencers like Andrew Tate revolve around an inherently harmful worldview.

Discipline is necessary in a system where men embrace domination, for example. Grit is essential in a world where mental health is seen as an unacceptable weakness. Self-improvement is necessary in relationships that objectify women as status symbols.

This kind of critical media literacy is something that can’t be taught as well as it can be experienced. We need to allow boys to explore the underlying connections between Andrew Tate's messages' positive and negative aspects. That’s what it looks like to empower boys as agents for change.

“We will find ready partners in boys themselves, who have a keen interest in being seen as they are, hearts beating loudly behind the masks they must wear.”

Andrew Tate costs a lot more than most boys think.

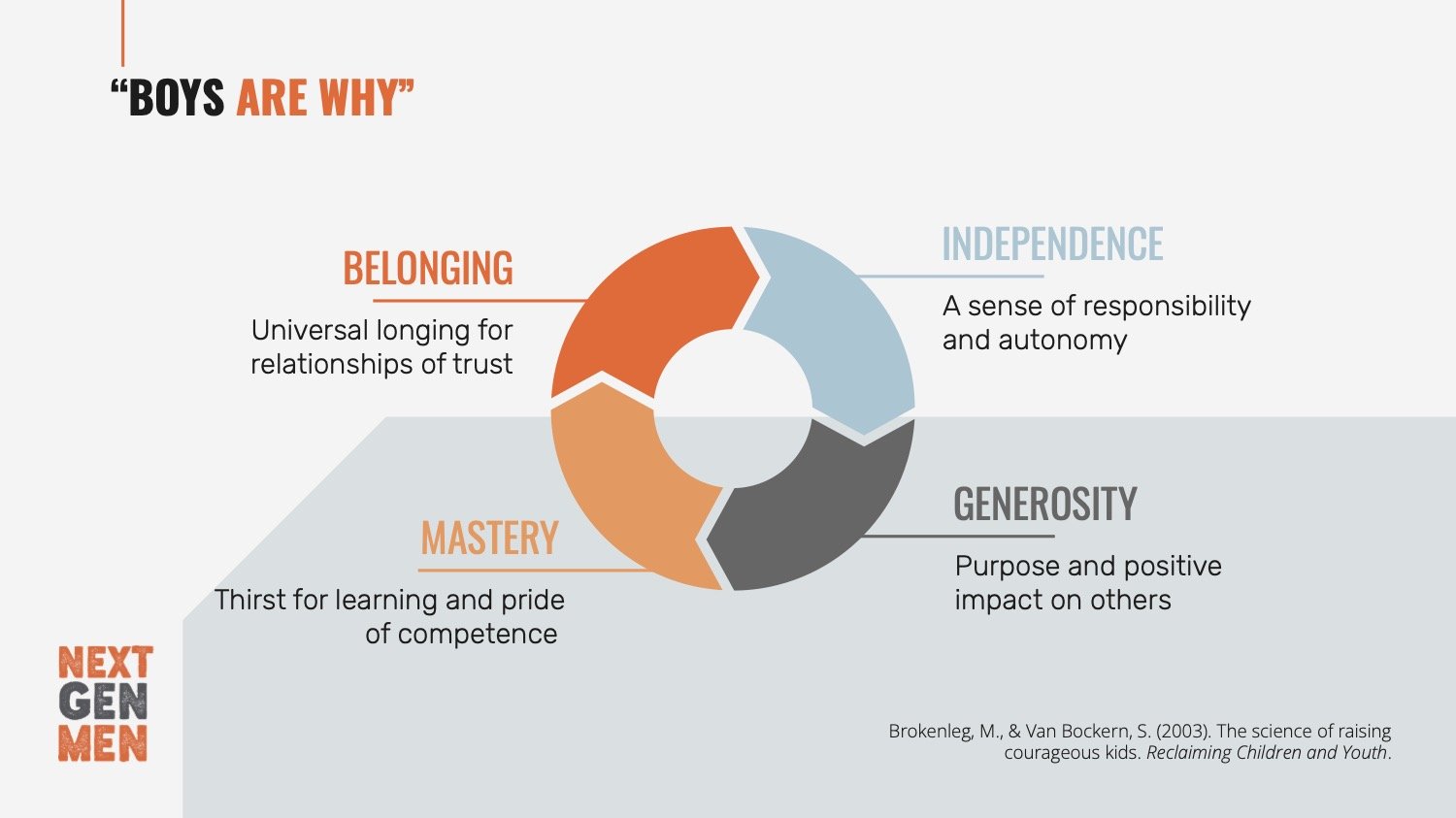

In the early 2000s, education researchers Martin Brokenleg and Steve van Bockern proposed a holistic approach to reclaiming young people by witnessing and responding to their core needs. Their Circle of Courage framework draws on Indigenous ways of understanding the sacred journey of childhood and embodies four core needs:

Belonging—the universal longing to be nurtured in relationships of trust and respect

Mastery—an innate drive to become competent and solve problems

Independence—the desire to ultimately make decisions free of adult control

Generosity—a sense of worthiness based on positive contribution to others’ lives

If schools don’t nurture these core values within the lives of young adolescent boys, they’ll look elsewhere to meet their needs.

That’s when they gravitate to anti-feminist influencers and other insular online spaces that offer a veneer of support. Boys might genuinely gain a sense of belonging by being part of the in-group led by Andrew Tate, Hamza Ahmed, Adin Ross and SNEAKO. Similarly, they might feel a sense of mastery in developing the mindset of discipline and achievement or independence in setting themselves against the perspectives of parents or educators.

What it costs them, however, is the spirit of generosity. There’s no way to reconcile Andrew Tate’s dog-eat-dog vitriol with the unselfish act of putting others first.

Generosity is a core need—not something nice to have on a good day, but a crucial part of how young people become who they’re meant to be. For boys to meet one core need at the cost of another is like giving up oxygen to drink water. It might as well cost everything.

We need to see the sacredness of children in our classrooms. Even the hard-edged, joking teenage boys who don’t think they need anything more than what they’ve got.

Especially them.

The best thing to do to tackle Andrew Tate at school is leverage rebellion itself.

More than anything, the dominance of influencers like Andrew Tate is built on the uncritical buy-in of their audience. Platforms like TikTok and YouTube are often less about being social and more about passively consuming algorithm-generated media. The best way to reclaim teenage boys, then, is to engage them as creators themselves.

Boys are much better positioned to challenge Andrew Tate’s messages than we are—they live it firsthand.

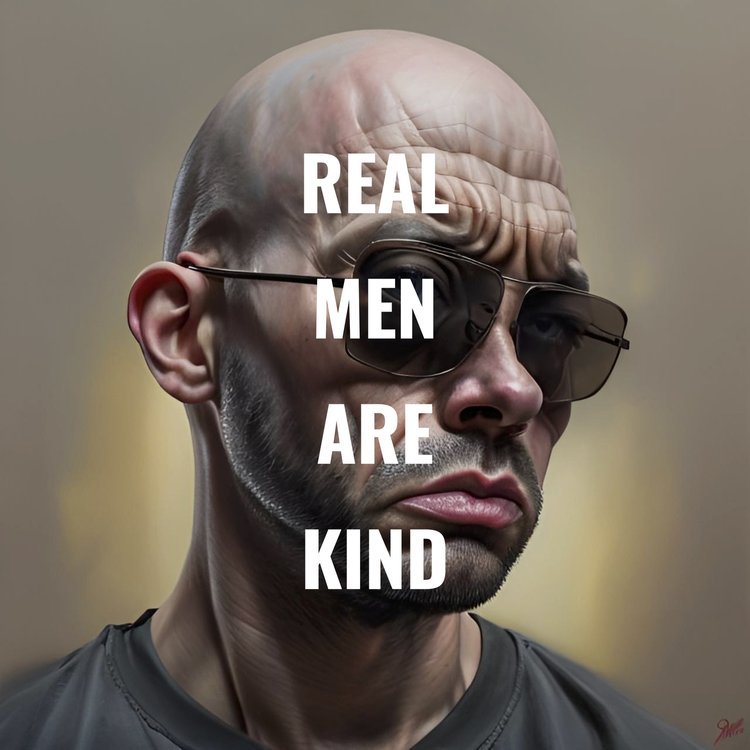

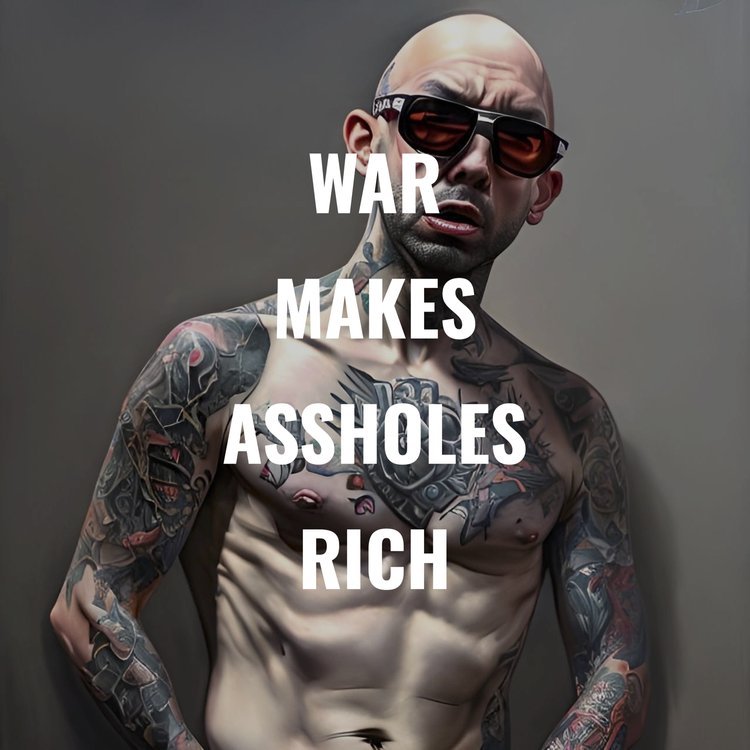

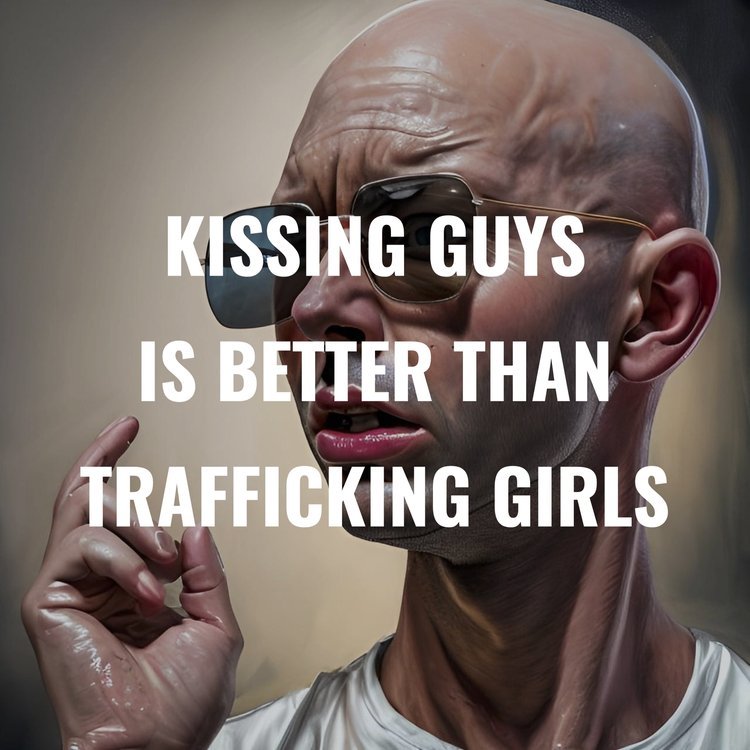

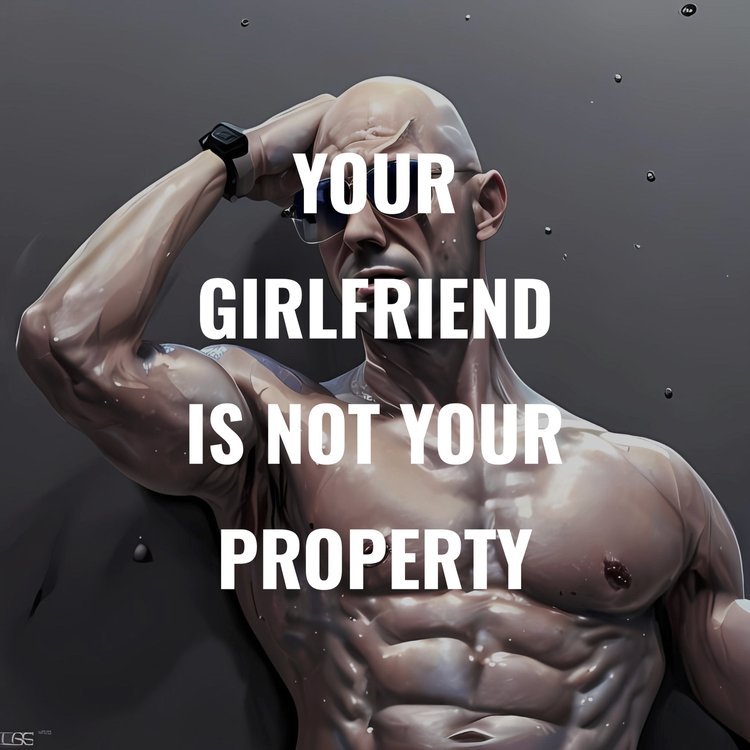

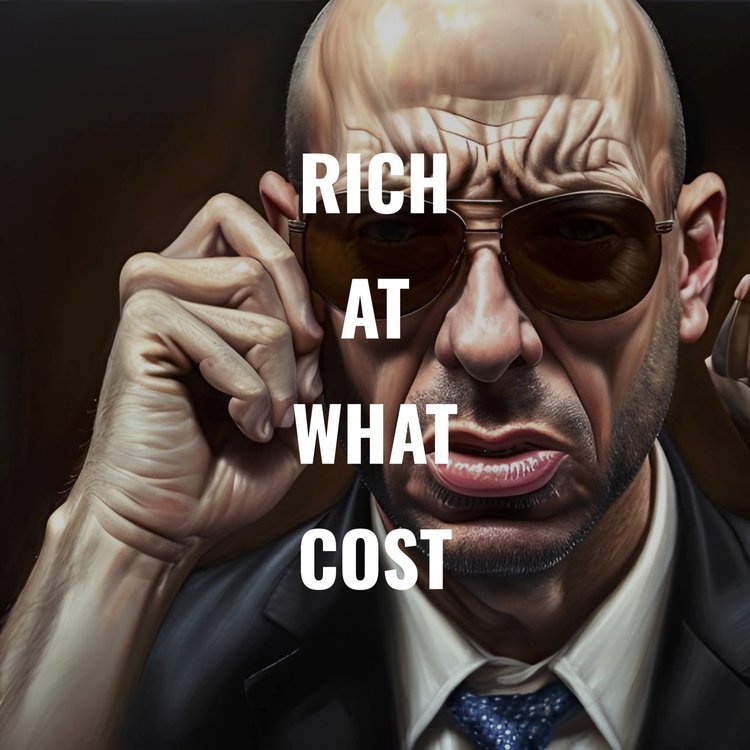

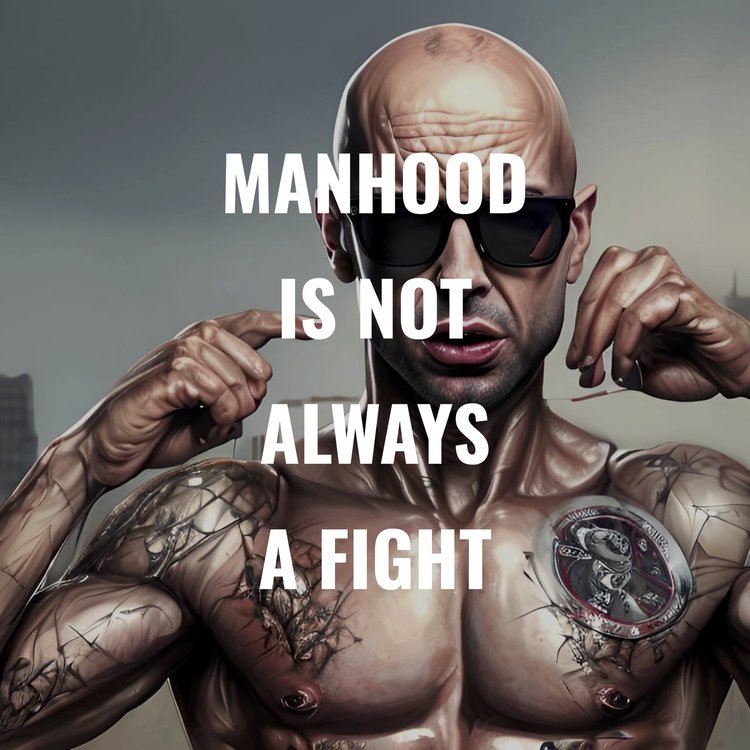

There are many ways to do this. At Next Gen Men, we’ve been developing an arts-based activity that positions Andrew Tate as an authority figure and empowers boys to contradict and subvert his messages. Students in this session use generative AI layered with culture-jamming tactics to create simple, powerful, no-holds-barred visual representations of where and how Andrew Tate should be called into question.

Their messages were clear when we first started co-developing this art project with teenage boys. “Real men are kind,” one of them wrote. “Your girlfriend is not your property,” added another.

Best of all, this is more than just a conversation. It’s an experience of reclaiming power—and that is not easily forgotten.

Take action: You can find the workshop we’ve dubbed Andrew Tate Would Hate This Art Project in the Next Gen Manual. For free. Go get ’em.

We wish schools could just sweep Andrew Tate under the rug and hope his cultural significance wanes with his prosecution. The reality is that the space he carved out is already being filled by those who continue to normalize and promote gender hierarchy and gender-based violence.

To be blunt, things are getting worse. Not better.

Now more than ever, we need to view the next generation of men with hope—not as problems to be fixed, or just as allies for girls and women, but as fellow stakeholders in the movement for gender justice.

By engaging boys with curiosity, guiding their examination of anti-feminist influences, nurturing their core needs and empowering them as changemakers, we leverage this cultural moment to recognize and ultimately stand against gender-based violence.

What are you waiting for?