Avoiding Prohibition-Era Tactics

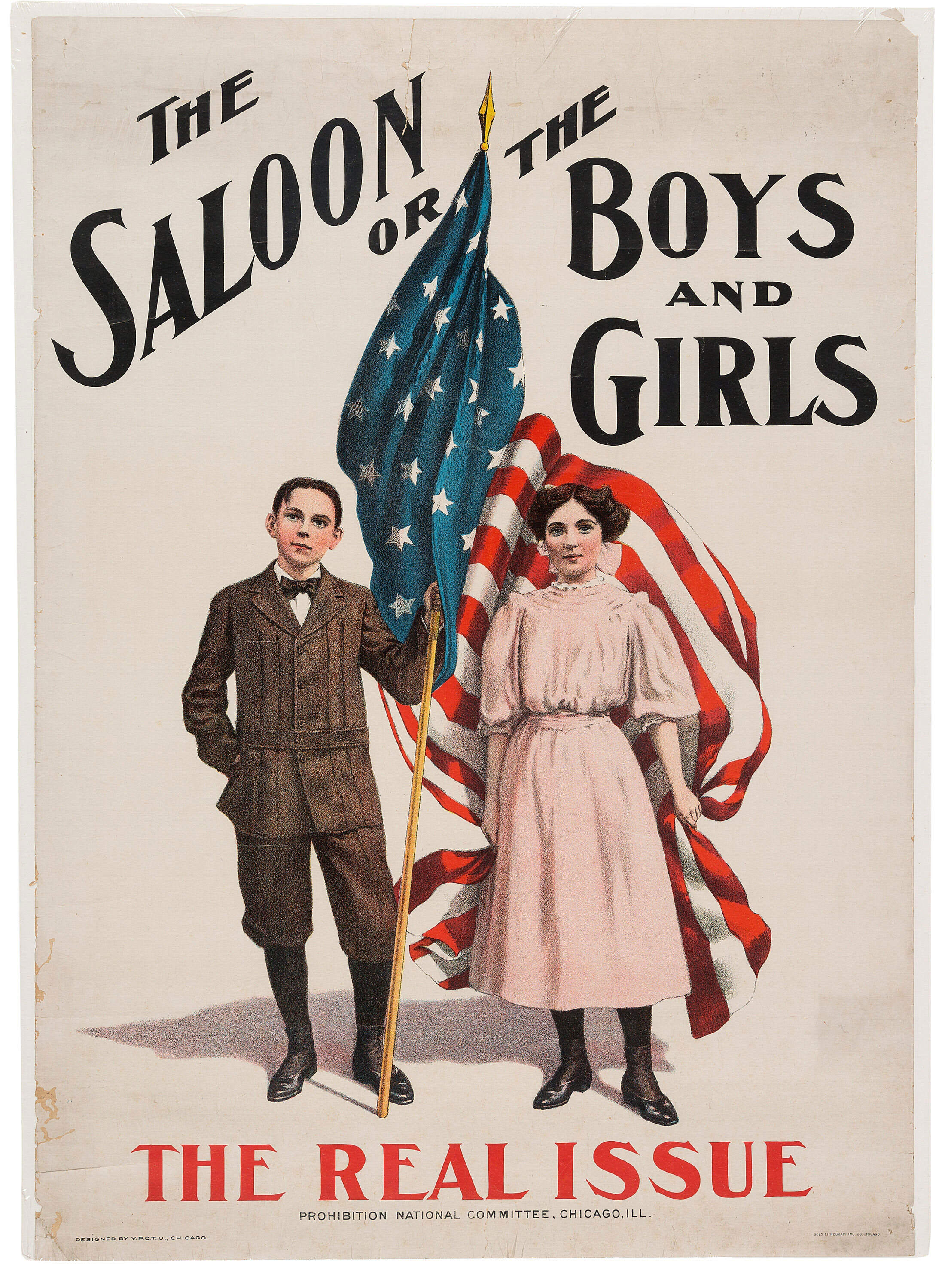

Poster from the Prohibition National Committee, ca. 1908

By Jonathon Reed

At an overnight camp several years ago, I encountered a group of preteen boys who had come up with their own version of Fight Club. They asked me to watch them play before I decided what to do.

As I watched the group, I realized two things: that the so-called ‘fight club’ was about physical closeness rather than animosity, and that an outright ban would just result in them keeping it going with even less supervision. So instead of shutting it down, I talked with them. Together, we acknowledged the importance of physicality in their relationships, we identified the crucial differences between play fighting and actual fighting, and we made a plan for how they would keep each other safe. By taking them seriously and honouring their burgeoning autonomy, I was able to stay in the room.

This is what I call anti-Prohibition tactics, because the Prohibition Era holds a lesson about why placing a ban isn’t the same as solving a problem.

In the late 19th century, leaders of the temperance movement in Canada and the United States began to link alcohol with violence, domestic abuse and poverty; and ultimately succeeded in passing laws that outlawed the consumption of alcohol. These laws, collectively known as Prohibition, arguably failed. Instead of better values, they resulted in speakeasies, bootleggers and other forms of organized crime.

Through my work with Next Gen Men, I regularly get questions from parents about regulating their son’s access to spaces that they see as exacerbating harmful norms of masculinity—things like video games, pornography and underage parties.

The first problem with banning boys is that it doesn’t work. Like the bootleggers of the 1920s, adolescents will always find alternative routes to where they want to be. If they access those spaces without our permission, all of a sudden there is distance between us. With distance comes distrust. How willing is a boy to seek help when things go wrong if he was breaking the rules in the first place?

The second problem is that an outright ban undermines boys’ capacity for positive masculinity. Yes, boys are impressionable and can be affected by ‘toxic’ masculinity. But they are also resilient and inherently capable of meeting the harshness and rigidity of harmful spaces with resistance, integrity and a commitment to their best selves.

As Michael Reichert put it, boys can feel overmatched and hopeless when left to their own devices in distrustful contexts with unyielding masculine norms. “But in quality relationships,” he writes, “equality, authenticity, and love blossom as boys grow into their visions for themselves as men.”

“They can and do resist all efforts to make them into something they are not. As they fight for who they are and want to become, they exercise the fundamental values of integrity and courage. As we nurture all of their human capacities, including integrity and courage, I am confident that boys will surprise us with their reinvention of a boyhood well suited to this new world.”

By continuing to engage boys in conversations about the norms and harms within adolescent masculinity, we demonstrate that we believe the best in them—and that we will be there alongside them when things go wrong.

By engaging sensitively and seriously with the Fight Club boys, I was able to role model what it looks like to communicate about safety, and stay in the room to make sure that conversation was taken to heart.

That’s worth more than any Prohibition.

Written by Next Gen Men Program Manager Jonathon Reed as part of Learnings & Unlearnings, a weekly newsletter reflecting on our experiences working with boys and young men. Subscribe to get Learnings & Unlearnings delivered to your email inbox.